We know, we know: It’s early to start thinking about hurricanes, and we’d really rather focus on this beautiful spring weather, too. But forecasters are already sounding the alarm about a potentially “super-charged” 2024 hurricane season, and here in Sarasota, the Climate Adaptation Center is gearing up for its annual hurricane forecast event on Thursday, April 4.

Led by meteorologist Bob Bunting, the center’s chief executive officer, the April event will not only share information about what we can expect from hurricane season this year, but will also feature talks by industry leaders about catastrophic risk, the future of infrastructure in Sarasota and what we can learn from Hurricanes Irma, Ian and Idalia—three storms that caused major problems in our area over the past seven years.

Ahead of the forecast, we talked to Bunting about three weather-related things to keep an eye on as hurricane season inches ever closer.

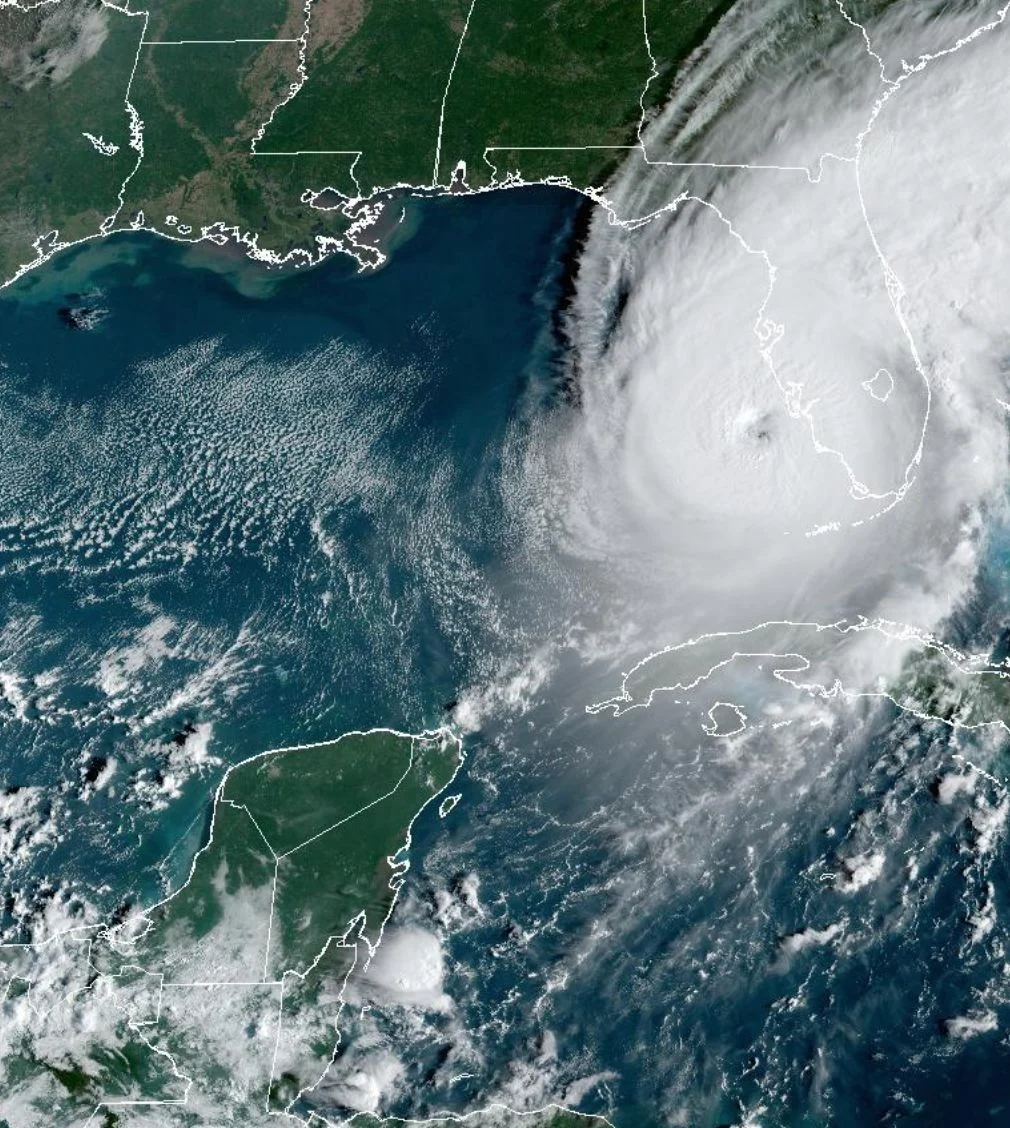

Sea Surface Temperatures

Warm waters are fuel for hurricanes. In August 2023, the temperature of the Gulf of Mexico broke 88 degrees Fahrenheit—the hottest ever recorded. In Key West, waters breached 100 degrees in July. “All other things being equal, a warmer ocean, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean allows the hurricanes that spin up to gather energy,” Bunting says.

El Niño, La Niña and Wind Shear

During an El Niño pattern, trade winds weaken and warm water is pushed back east. That causes the Pacific jet stream to head south, which creates dryer and warmer weather in the northern U.S. and Canada. But here on the Gulf Coast, we experience wetter, cooler weather. (Remember those winter storms?)

Like El Niño, a La Niña pattern affects the jet stream—and it specifically affects wind shear, which has a direct relationship to hurricane strength and formation. Right now, forecasters from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center put the odds of La Niña developing this summer at 62 percent.

“El Niño peaked in February and it’s rapidly diminishing now, which means less wind shear in the Atlantic,” Bunting says. “Wind shear is the enemy of hurricanes.” Wind shear disrupts the energy around a hurricane, causing it to become less organized. But if there’s little to no wind shear, hurricanes can easily grow—and, potentially, turn into the types of monster storms we’ve been seeing over the last few years. Bunting cites Hurricane Otis, which slammed into Mexico after morphing from a storm with 55-mile-per-hour winds into a major hurricane with 165-mile-per-hour winds in just 24 hours, as a prime example.

“If we have a situation where we have really warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear [due to La Niña], those are two major ingredients coming together in a way that would support stronger hurricanes,” Bunting says.

African Storms

If dry African air blows dust from the Sahara Desert over the Atlantic, it decreases the possibility of hurricanes becoming severe. (We’ve seen this in recent years.) But if there’s moisture in the air, small storm systems that form in central Africa and move into the Atlantic can potentially morph into bigger, stronger storms.

“Even 10 years ago, we couldn’t predict these African storms,” Bunting says. “Now we have long-term, skillful models that can predict the kind of monsoonal activity that causes them, and we can run them into August or September.” Bunting is quick to clarify that these models are not going to tell forecasters what day a storm will form, but, over the course of a month, they can show that there’s more moisture in the air in the hurricane region than there was the previous year.

“All of these things offer clues about what could happen during a hurricane season,” Bunting says. “If I were a city’s emergency manager, I would be asking myself, ‘Should we be doing what we always do ahead of hurricane season, or can we do more?’ Or, ‘What are additional things we can do right now to help lower the risk of life-threatening situations and severe damage during a storm?’”

“We’re moving into a high-threat situation,” he continues. “That doesn’t mean we’re going to be wiped out this year—just that the risk of something more serious is higher than it would be in a normal summer.”